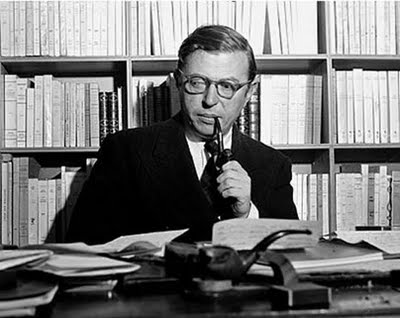

Jean-Paul Sartre

Sartre — apostle of absurdity

Jean-Paul Sartre may be the most famous atheist of the 20th century. As such, he qualifies for anyone’s short list of “pillars of unbelief.”

Yet he may have done more to drive fence-sitters toward the faith than most Christian apologists. For Sartre has made atheism such a demanding, almost unendurable, experience that few can bear it.

Comfortable atheists who read him become uncomfortable atheists, and uncomfortable atheism is a giant step closer to God. In his own words, “Existentialism is nothing else than an attempt to draw all the consequences of a coherent atheistic position.” For this we should be grateful to him.

He called his philosophy “existentialism” because of the thesis that “existence precedes essence.” What this means concretely is that “man is nothing else than what he makes of himself.” Since there is no God to design man, man has no blueprint, no essence. His essence or nature comes not from God as Creator but from his own free choice.

There’s profound insight here, though it is immediately subverted. The insight is the fact that man by his free choices determines who he will be. God indeed creates what all men are. But the individual fashions his own unique individuality. God makes our what but we make our who. God gives us the dignity of being present at our own creation, or co-creation; He associates us with Himself in the task of co-creating our selves. He creates only the objective raw material, through heredity and environment. I shape it into the final form of myself through my free choices.

Unfortunately, Sartre contends that this disproves God, for if there were a God, man would be reduced to a mere artifact of God, and thus would not be free. He constantly argues that human freedom and dignity require atheism. His attitude is like that of a cowboy in a Western, saying to God as to an enemy cowboy: “This town ain’t big enough for both you and me. One of us has to leave.”

Thus Sartre’s legitimate concern with human freedom and his insight into how it makes persons fundamentally different from mere things lead him to atheism because (1) he confuses freedom with independence, and because (2) the only God he can conceive of is one who would take away human freedom rather than creating and maintaining it — a sort of cosmic fascist. Furthermore, (3) Sartre makes the adolescent mistake of equating freedom with rebellion. He says freedom is only “the freedom to say no.”

But this is not the only freedom. There’s also the freedom to say yes. Sartre thinks we compromise our freedom when we say yes, when we choose to affirm the values we’ve been taught by our parents, our society, or our Church. So what Sartre means by freedom is very close to what the beatniks of the `50s and the hippies of the `60s called “doing your own thing,” and what the Me generation of the `70s called “looking out for No. 1.”

Another concept Sartre takes seriously but misuses is the idea of responsibility. He thinks that belief in God would necessarily compromise human responsibility, for we would then blame God rather than ourselves for what we are. But that’s simply not so. My heavenly Father, like my earthly father, is not responsible for my choices or the character I shape by means of those choices; I am. And the fact of my responsibility no more disproves the existence of my heavenly Father than it disproves the existence of my earthly father.

Sartre has a keen awareness of evil and human perversity. He says, “We have learned to take Evil seriously…Evil is not an appearance…Knowing its causes does not dispel it. Evil cannot be redeemed.”

Yet he also says that since there is no God and since we therefore create our own values and laws, there really is no evil: “To choose to be this or that is to affirm at the same time the value of what we choose, because we can never choose evil.” So Sartre gives both too much reality to evil (“Evil cannot be redeemed”) and too little (“We can never choose evil”).

Sartre’s atheism does not merely say that God doesn’t exist, but that God is impossible. He at least pays some homage to the biblical notion of God as “I Am by calling it the most self-contradictory idea ever imagined, “the impossible synthesis” of being-for-itself (subjective personality, the “I”) with being-in-itself (objective eternal perfection, the “Am”).

God means the perfect person, and this is for Sartre a contradiction of terms. Perfect things or ideas, like Justice or Truth, are possible; and imperfect persons, like Zeus or Apollo, are possible. But the perfect person is impossible. Zeus is possible but not real. God is unique among gods: not only unreal but impossible.

Since God is impossible and since God is love, love is impossible. The most shocking thing in Sartre is probably his denial of the possibility of genuine, altruistic love. In place of God, most atheists substitute human love as the thing they believe in. But Sartre argues that this is impossible. Why?

Because if there is no God, each individual is God. But there can be only one God, one absolute. Thus, all interpersonal relationships are fundamentally relationships of rivalry. Here, Sartre echoes Machiavelli. Each of us necessarily plays God to others; each of us, as the author of the play of his own life, necessarily reduces others to characters in his drama.

There is a little word which ordinary people think denotes something real and which lovers think denotes something magical. Sartre thinks it denotes something impossible and illusory. It is the word “we.” There can be no “we-subject,” no community, no self-forgetful love if each of us is always trying to be God, the one single unique I-subject.

Sartre’s most famous play, “No Exit,” puts three dead people in a room and watches them make hell for each other simply by playing God to each other—not in the sense of exerting external power over each other but simply by knowing each other as objects. The shocking lesson of the play is that “hell is other people.”

It takes a profound mind to say something as profoundly false as that. In truth, hell is precisely the absence of other people, human and divine. Hell is total loneliness. Heaven is other people, because heaven is where God is, and God is Trinity. God is love, God is “other persons.”

Sartre’s tough-minded honesty makes him almost attractive, despite his repellant conclusions like the meaninglessness of life, the arbitrariness of values and the impossibility of love. But his honesty, however deep it may have lodged in his character, was made trivial and meaningless because of this denial of God and thus of objective Truth. If there is no divine mind, there is no truth except the truth each of us makes of himself. So if there’s nothing for me to be honest about except me, what meaning does honesty have?

Yet we cannot help rendering a mixed verdict on Sartre, and being gratified by his very repulsiveness — for it flows from his consistency. He shows us the true face of atheism: absurdity (that’s the abstract word), and nausea (that’s the concrete image he uses, and the title of his first and greatest novel).

“Nausea” is the story of a man who, after arduous searching, finds the terrible truth that life has no meaning, that it’s simply nauseating excess, like vomit or excrement. (Sartre deliberately tends toward obscene images because he feels life itself is obscene.)

We cannot help agreeing with William Barrett when he says that “to those who are ready to use this [nausea] as an excuse for tossing out the whole Sartrian philosophy, we may point out that it is better to encounter one’s existence in disgust than never to encounter it at all.”

In other words, Sartre’s importance is like that of Ecclesiastes: He asks the greatest of all questions, courageously and unswervingly, and we can admire him for that. Unfortunately, he also gives the worst possible answer to it, as Ecclesiastes did: “Vanity of vanity, all is vanity.”

We can only pity him for that, and with him the many other atheists who are clear-headed enough to see as he did that “without God all things are permissible” — but nothing has meaning.

This is Part 5 of a 6-part series, The Pillars of Unbelief, by Dr. Kreeft, originally ran in The National Catholic Register, (January – February 1988).

Please help us in our mission to assist readers to integrate their Catholic faith, family and work. Tell your family and friends about this article using both the Recommend and Share buttons below and via email. We value your comments and encourage you to leave your thoughts below. Thank you! – The Editors