Toronto’s Globe & Mail (July 19, 2008) featured a sociological look into women who had abortions. Titled “The Hidden Abortion Issue,” it explored why, though abortion has been unrestricted in Canada for two decades, so few women who have undergone abortion ever talk about it, even with close friends. Journalist Cate Cochran does not provide any answers to the question she poses, and seems slightly perplexed that in “liberal” Canadian society there remains a “stigma around the procedure that dare not speak its name.”

Toronto’s Globe & Mail (July 19, 2008) featured a sociological look into women who had abortions. Titled “The Hidden Abortion Issue,” it explored why, though abortion has been unrestricted in Canada for two decades, so few women who have undergone abortion ever talk about it, even with close friends. Journalist Cate Cochran does not provide any answers to the question she poses, and seems slightly perplexed that in “liberal” Canadian society there remains a “stigma around the procedure that dare not speak its name.”

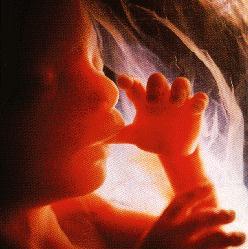

If abortion is simply a “choice,” as pro-choice advocates never tire of reiterating, why is it still associated with a stigma and followed by feelings of guilt, a sense of shame and regret, and a brooding silence? The notion of being “pro-choice,” which simplifies abortion propaganda into simple-mindedness, is so ingrained in the minds of abortion advocates that they have accepted the rhetoric and left out the reality.

One woman interviewed, who had undergone an abortion at the age of 33, expressed her dilemma in the following way: “I’m not entitled to the grief that I have because I chose my loss.” She could not have articulated the matter more succinctly or more pointedly. The root of her dilemma, though one not expounded in the article, is her unexamined belief that she could isolate choice from any consequence that would be undesirable. The radical weakness of pro-choice advocates is that they do not understand the basic dynamic of choice. Making a choice, especially one that is fraught with moral implications, is like throwing a stone into the water. There is going to be a ripple effect. Choosing is not like directing a laser beam that focuses on one specific object and excludes everything else.

Choice has consequences. It is naïve in the extreme to think that a moral choice is so pin-pointed that it produces but one consequence, namely the one that is desired. A better word than “consequence,” however, is repercussion. A consequence is something that a cause produces. It may be innocuous. As a consequence of the rain, the ground is wet. But a repercussion is a consequence that comes back and bites you. Abortion not only has consequences, it has repercussions. And these repercussions are well documented in the medical journals.

Why is this so? And how can people fall for the obvious illusion that certain moral choices, such as abortion, will not have undesirable repercussions? The presumed isolation of choice from repercussion is based on a more elementary isolation of the ego from the person. Person designates the whole self, body and soul, individuality and communality, present and future, the mortal and the immortal. The ego, by comparison, is a kind of Euclidean point. It is an island of vanity cut off from the continent of reality. The ego is the person in a severely truncated state.

Our primal parents made a choice and brought about an avalanche of repercussions that have resounded throughout history, often with catastrophic effect. Their descendents can hardly commend them for being “pro-choice”. Their choice brought about, among other things, shame, the piercing sense that they had made a disgraceful choice, one that was not worthy of them, one that was not true to their whole nature as persons. The freedom they thought their choice would bring them turned out to be slavery. The elevated status they sought proved to be a Fall.

The ego sees things very clearly because it sees them simplistically and therefore unrealistically. It envisions but one consequence per choice, the desirable one, and no repercussions. Choosing abortion, consequently, is simply choosing to end and unwanted pregnancy. What could be simpler? So where did the grief come from? The grief was latent in the equation at the very beginning, something that the person would have noticed, but not the ego. The ego sees only what it wants to see. Everything is baby simple. The person sees much more and understands how a particular choice, though aimed at one desirable result, can unleash a train of tragedies. “Oh what a tangled web we weave when first we practice to deceive,” warned Sir Walter Scott. In Homer’s Iliad we find these searing words: “Hateful to me as are the gates of hell, Is he who, hiding one thing in his heart, Utters another.”

The problem that the newspaper ignored is essentially anthropological. Who am I? Am I an alienated ego who can choose from that narrow ledge and not experience undesirable repercussions? Or am I a person who must honor my humanity, my womanhood or my manhood, my family and friends, my body, my progeny, my God?

A woman chooses abortion and as a result, grief chooses her. It is inevitable that some women, after undergoing an abortion, would become members of a group that calls itself “Victims of Choice”. In truth, they were victims of a false anthropology, one that seduced them into thinking that they were merely egos, and that reality is merely their reflecting mirror.

A person, most assuredly, is “pro-choice”. But he chooses from the broad base of his personality and chooses life.

After reading Cate Cochran’s dreary profiles of aborting women, I turned to Bernard Mandelbaum’s thoughtful book, Choose Life (Random House, 1968):

And this is what it means to choose life:

It means:

- gaining possession of knowledge of ourselves, our fellow-men and of the universe;

- experiencing the beauty of Creation of a tree, of the sky, of a song;

- building the structure of our lives on the foundations of wisdom: wisdom of the past and of the present.

For these enlarge us.

It means:

- giving of our thoughts, our feelings, and our time . . . giving of ourselves . . . to our children, to a wife or husband, to a friend, a neighbour;

- meeting our deepest responsibilities in the community, in our country, and in the brotherhood of nations;

- sharing the pain and suffering of others, knowing well that “they who sow in tears shall reap in joy.” (Psalm 126:5).

For these involve us.

It means:

- fighting evil,

- nurturing an ideal.

- fashioning character,

All of which extend our impact and meaning in the world beyond our own lives, joining us with the generation of men, as with our Maker.

For these continue us.

In choosing life, then, we choose to enlarge, involve, and continue ourselves. It is a creative choice.

The word “choice,” unfortunately, has been hijacked and twisted out of shape to suit an anti-life mentality. This tactic creates the infelicitous and illogical impression that those who choose life are somehow “anti-choice”. We should choose life, surely. Yet our attitude toward life should have more vigor than it being merely an object of choice. We should choose life with unwavering decisiveness. What decisiveness adds to choice is the notion of commitment and continuity. The goodness of life warrants our decisiveness because it is ongoing. In fact, it is eternal. One cannot, in the same way, be decisive about a choice to kill. The point of killing is to terminate or put to an end. One, therefore, cannot be committed (decisively) to something that one wills not to exist.

We are made for life. To put an end to one’s own flesh and blood strikes against our nature, even if it may agree with our ego. Decisiveness in the service of life requires a degree or intensity of choice that is unknown to people who identify themselves as being “pro-choice”.

George Weigel, author of the definitive biography of Pope John Paul II, Witness to Hope, states that the Holy Father’s papacy had been “a one-act drama” involving “the tension between various false humanisms that degrade the humanity they claim to defend and exalt, and the true humanism to which the biblical vision of the human person is a powerful witness.”

The “pro-choice” position is based on a false humanism that exalts the ego and suppresses the person. It is a form of humanism that does not come to terms with the wholeness of the human being. Being human means far more than simply being a human being. It means being faithful to who one is as a whole person. All human beings are human beings. But human beings do not always behave in a way that is consistent with their humanity. Hence, we distinguish between actions that are “humane” and those that are “inhumane”. In either case, choices are made. But choice itself is not self-vindicating. Choice is justified when it is consistent with one’s humanity and directed to a good.

The false humanism that undergirds abortion usually remains unexplored and therefore undiscussed. There is a stigma and a shame attached to abortion not because it is imposed from the outside, but because it is a violation of the self, a decision not to make the generous choice from the broad base of one’s humanity.

The question that Socrates continued to ask—“Who am I?”—remains, to a large extent, incorrectly answered. We are persons, not alienated egos. As persons, we choose to embark on the vast ocean of life; as egos, we miss the boat.