This weekend we celebrate Father’s Day throughout the United States. It’s a relatively recent feast, made a permanent national holiday on the third Sunday of June only in 1972 when it was signed into law by President Nixon. President Lyndon Johnson had given the first presidential proclamation honoring fathers only six years prior. Mother’s Day, by contrast, was proclaimed by President Woodrow Wilson in 1914 to be held on the second Sunday of May. The earlier celebration for mothers is partially explained by the desire to honor the work of moms at a time in our nation’s history when women and their contributions to society were often widely underappreciated. But the length of the delay for fathers may also explain how the role of men precisely as fathers has similarly been underappreciated.

This article originally appeared in The Anchor, the weekly newspaper of the Diocese of Fall River, Mass, on June 14, 2019 and appears here with the kind permission of the author.

Social science has been documenting in recent decades just how important the role of fathers is in raising children to be integrated adults. When kids grow up without a father in the home, they experience much higher rates of school suspensions, staying back in school, dropping out of school, child poverty, youth violence, crime, incarcerations, drug use, behavioral disorders, obesity, running away from home, homelessness, sexual abuse, promiscuity, teen pregnancy, and suicide. This is particularly concerning when 43 percent of children in the US now live without a father in the home.

The future Pope Benedict XVI said in a March 2000 speech in Palermo, “The crisis of fatherhood we are experiencing today is an element, perhaps the most important element, threatening man in his humanity.” The crisis, he said more specifically, is a “dissolution of fatherhood,” flowing from reducing paternity to a biological phenomenon without its human and spiritual dimensions. Fathers are treated as superfluous, seen in the explosion of what sociologists now term sperm dads, absent dads, dead-beat dads, visiting dads, nice-guy dads, and various other descriptors for fathers who have no decisive role in protecting, providing for, rearing and mentoring the children they’ve begotten.

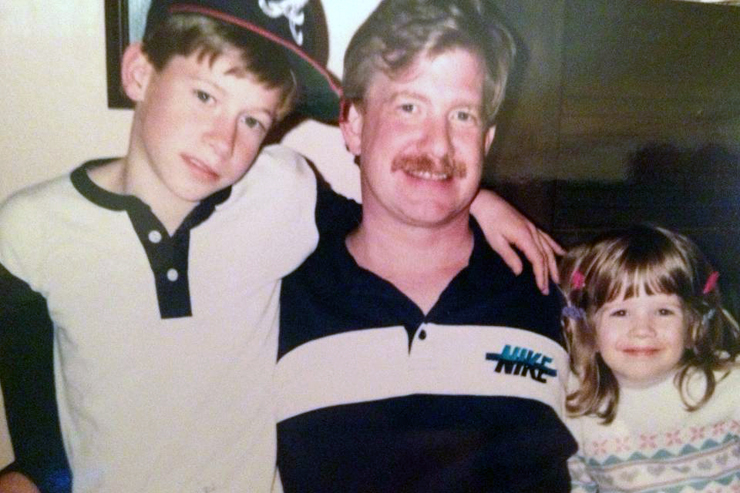

When kids, however, are blessed with a dad who has made a lifetime commitment to their mom and to them, when fathers live up to their calling, they in general do much better. That’s why on this Father’s Day it is so important to celebrate and thank dads who have lovingly prioritized their responsibilities to their families. But it’s also why it’s key to celebrate and promote fatherhood in general, not just for the good of men, but also for the good of the women who count on their capacity for faithful love and for the children who so much need both parents in a committed alliance.

In the promotion of fatherhood and the formation of men to be good dads, the Church has much to offer. Practically, there are organizations like the Knights of Columbus as well as an explosion of parish men’s groups and diocesan conferences to help men support each other as sons, brothers, husbands and dads. Theologically, there is a goldmine of wisdom about the paternal meaning of man’s masculinity found in what Jesus revealed about God the Father and in his own spiritual fatherhood that can help men.

Pope Benedict in a 2012 General Audience spoke about the greatness of fatherhood in the divine plan. “Perhaps people today,” he said, “fail to perceive the beauty, greatness and profound consolation contained in the word ‘father’ with which we can turn to God in prayer because today the father figure is often not sufficiently present and all too often is not sufficiently positive in daily life. … From Jesus himself, from his filial relationship with God, we can learn what ‘father’ really means and what is the true nature of the Father who is in heaven. … In the Gospel Christ shows us who is the father and as he is a true father we can understand true fatherhood and even learn true fatherhood.”

Jesus came to reveal God the Father and the depth of his love for his children. He showed us how the Father takes delight in his children (Mt 3:17), loves unconditionally (Mt 5:45), is provident and responsible (Mt 6:26), pays close and caring attention (Mt 6:8), forgives (Lk 6:36, 15:11-32), teaches (Mt 11:25-26, 16:17, Jn 6:44), lovingly disciplines (Heb 12:5-11), works hard (Jn 5:17, 36), and shares his life (Jn 6:40), giving an example for all earthly dads.

Likewise Jesus, the icon of the Father, the New Adam and the father of the restored creation, exercised his own spiritual paternity in becoming the principle of the new life we receive in the Sacraments through his passion, death and resurrection.

It is in this sense that priests — who act “in the person of Christ” in the sacraments — exercise Christ’s fatherhood and are appropriately called “fathers.” Theirfatherhood cannot be reduced merely to spiritually generative sacramental actions, but is meant to flow into fatherly identity and behavior, particular in the commitment they make spiritually to protect, provide for, rear and mentor the spiritual children entrusted to them. When priests are reduced to ecclesiastical functionaries who never form authentic fatherly bonds with the individuals and families whose baptisms, weddings, and funerals they celebrate, there is a huge problem.

That’s why recent remarks by Cardinal John Dew, Archbishop of Wellington, New Zealand, are so myopic and potentially harmful. In an April 4 column, he praised an article by Fr. Jean-Pierre Roche in La Croix International that aruged that we should stop calling priests “Father.” He recited Roche’s three arguments: Jesus says we should call no one on earth our father (Mt 23:8-9); calling someone “father” necessarily places one in the inferior position of a child when we’re all supposed to be equal; and denoting a “father” inevitably fosters a relationship of dependence and obedience. In response to Pope Francis’ call to fight against clericalism, Cardinal Dew said, ceasing to call priests “father” or him “Eminence” or “Cardinal” “might seem like a very small thing to do, but it may be the beginning of the reform in the Church.”

The reform of the Church is not going to come from calling the Pope “Frank,” or the Archbishop of Wellington “John,” or the pastor of one’s parish by his baptismal moniker. It’s not going to come from the verbal dissolution of the spiritual paternity of the priesthood, but rather, from the buttressing of the authentic fatherly nature of the priestly call. Clericalism is an abuse of spiritual fatherhood just as much as authoritarianism is an abuse of natural fatherhood. The remedy is not to eliminate the oral reminders of fatherly identity but to purify the exercise of fatherhood. As the wise aphorism goes, abusus non tollit usum: the misuse of something is no argument against its proper use.

In regard to the arguments cited, Jesus’ words to call no one father, or rabbi, or master were meant to communicate that no one should seek to replace God, who is our principal father, teacher and master. We can still call our dads father, our instructors teacher and our rabbis rabbi, provided that we’re not treating them as if they were God. The context shows that Jesus was correcting the Pharisees for prioritizing a separate set of allegiances based on rabbinical tradition over what God himself had revealed. Jesus himself uses the word father several times, when he speaks about not loving “father or mother” more than him and of leaving one’s “father” to follow him (Mt 10:37; Mk 10:29). Jesus’ example, as well as St. Paul’s after him, shows us the use of father to refer to spiritual fatherhood, like that exercised by priests. Jesus cites Abraham, our father in faith, as “Father Abraham” in a parable. St. Paul tells the Corinthians, “In Christ Jesus I became your father through the Gospel” (1 Cor 4:15).

Does calling someone a “father” necessarily place the spiritual son or daughter in an inferior position or create a situation of dependence and obedience? Perhaps when we’re dealing with infants, but not with adults. When adults call their parents “Mom” and “Dad,” they’re not referring to a power-axis — in many case, the children are the ones making the decisions — but employing a term of fact, endearment, and reverence. Similarly when Catholics use father, they’re not employing it in the sense of the ancient, brutal Roman paterfamilias. They’re recognizing the priest’s role to provide for, protect, and guide them spiritually.

That’s why on this Father’s Day, in addition to thanking our earthly dads, we should also be celebrating God the Father and the spiritual fatherhood of Jesus — both quite fittingly on Holy Trinity Sunday — as well as the way priests are called by both to cooperate with the Holy Spirit in becoming spiritual fathers after the image of Father and Son.

Please share this post on Facebook and other social media below: