Photography © by Mark Armstrong

In December, 1531, a man we know today as St. Juan Diego began an encounter with Our Blessed Mother that reverberates to this day. The fifty-six-year-old Juan Diego was a simple, humble, mat-weaver by trade when he came upon Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico. His indigenous Aztec name, Cuauhtlatatzin, means “the eagle that talks.” Juan’s encounter with Mary would eventually lead to the end of the Aztec culture that depended for centuries on the slaughter of innocent human beings.

All the events of the miracle of Our Lady of Guadalupe took place in what now is part of the huge modern metropolis of Mexico City, Mexico. Today, the greater Mexico City population of 21.3 million people makes it the largest metropolitan area of the Western Hemisphere, the tenth-largest agglomeration, and the largest Spanish-speaking city in the world. The mile-high city of Mexico is surrounded by volcanoes and sits in a fertile valley.

Five hundred years ago, the Aztec society was thriving in Mexico and Central America; at the pinnacle of its power. Their island city of 250,000 people was one of the most populous cities in the world at the time. Tenochtitlan was a large Mexica city-state on an island in Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico. Founded on June 20, 1325, it was teeming with zoos, palaces, stoned-lined streets, pyramids, floating flower and vegetable gardens with as advanced a culture the world had ever seen.

After twelve years of research on Our Lady of Guadalupe, I have cobbled together a lot of information about this remarkable historical event. I enjoy giving a presentation to schools, churches and others about the story. There are three parts to this remarkable Marian apparition story; the first involves the landing of the Spanish in 1519, next involves the apparitions themselves in December, 1531, and finally what it all means for us today—five hundred years later.

The Landing of the Spanish in 1521

The Spanish landed on the east coast of Mexico on Good Friday, April 22, 1519, and celebrated Easter Mass on the shores of what know today as Veracruz, Mexico. The Spanish leader, Hernán Cortés, commanded eleven Spanish ships, nearly five hundred soldiers with twenty horses, and a small number of arms and cannons. Cortés and his men had many motives for conquering these lands. Some of the Spanish were looking for gold, silver and other treasures; others were looking to bring people, land and souls into the Catholic Church. But when these soldiers came face-to-face with the reality of the slaughter of human sacrifice, they were all in agreement to put an end to this culture of blood and death. There were gold and thrill seekers among the Spanish, but the brutal culture of death that demanded the killing of enemies, friends and family shocked Cortés and his battle hardened soldiers.

In fact, the first Aztec emissaries who arrived to meet the white Spanish solders who came on “floating islands” and rode great “armored beasts” believed Cortés himself was one of their gods. The Aztecs believed that Cortés was their god Quetzalcoatl, returning as foretold hundreds of years before. According to Aztec prophecies, Quetzalcoatl, once vanquished, promised to return to bring to his people the knowledge of the one true god and to end human sacrifice. To appease Cortés the Aztecs invited him to witness the slaughter firsthand. The Aztecs prepared a feast and served him powdered human blood sprinkled on his food, which Cortés spat out and rejected. Eventually Cortés and his men watched the Aztecs cutting out and eating the hearts of their victims, dismembering them and pitching their body parts off the tops of stone pyramids and saw the crowds cheering below at the foot of these temples of death.

There are wide estimates of how many innocent people were slaughtered over the course of thousands of years throughout what would become Mexico. By the late 1400s, during the reign of the Aztecs, each community throughout Mexico was required to offer one thousand people each year to the god Huitlopchtli, the god of death, sun and war. But the slaughter did not end there. Throughout the year, the Aztecs had scores of gods that demanded human sacrifices year in and year out. The demand for fresh blood and the gory spectacle were ingrained in their culture. Men, women, friend, foe, royalty, commoners all participated in the killings. One Mexican historian estimated that one out of five children was sacrificed. Sometimes entire tribes were exterminated by sacrifice. Even the royalty offered members of their own families to be killed.

These gory public executions atop the pyramids were performed by the priestly class for the masses to witness. With the sounds of beating drums, screaming voices, howls and whistles, the sacrificial victims, sometimes screaming themselves, were marched up the steep steps to the tops of the giant pyramids to the bloodstained stone platforms. The Aztec priests, dressed in satanic-looking dark costumes, would hold the victims’ arms and legs apart and then bend their bodies backwards over convex slabs of stones.

As the crowds cheered and the deadly drumbeat intensified, one of the priests would take a sharp blade of black volcanic glass and gut the victim open. As the blood sputtered out, the heart was still beating as it was held up for the cheering crowds to see. Sharp stone blades would then cut off the victim’s head, arms and legs. Then each heart was eaten voraciously by the killers atop the pyramid as the rest of the victim’s body parts were hurled down the steps of the pyramids to the crowds below. During new pyramid dedications, tens of thousands of human beings were slaughtered in this manner over the course of several days.

Cortés and his men had never imagined that there could be such an advanced society living with so great an evil. It was beyond their comprehension. Some of the Spaniards, captured in the battles to come, became victims of the human sacrifice they were determined to eradicate. It took almost three years of bloody conflict for the war to end and for the Spanish to declare victory over the Aztecs. While the war was officially over, there were many insurrections and attempts to return to the “old ways” and incidents of human sacrifices continued for nearly 10 years after official hostilities had ended.

Our Lady of Guadalupe and St. Juan Diego

Nearly twelve years after the Spanish landed and nine years after the end of hostilities, there had been only limited success with converting the Aztecs and other tribes to the Catholic faith. By 1531, there were only a few hundred true converts. The Spanish tried to translate, for the most part unsuccessfully, the tenets of the Catholic faith to a people who did not have a written language. Suddenly, and quite unexpectedly for all involved, that all changed in December, 1531, when one of the first converts to the faith, Juan Diego, encountered Our Lady of Guadalupe.

On that early December morning in 1531, Juan Diego walked passed by Tepeyac Hill, a few miles from church to attend Mass there. Suddenly the sky became bright and he heard singing on top of the hill, like the songs of various birds.

At the end of the song, as Juan Diego looked toward the hill, he heard a woman call out to him. There, he saw a young lady whose clothes shone with the radiance of the sun. He prostrated himself in front of her. When she asked Juan where he was going, he replied that he was going to church to hear the sermons of the friars. The woman identified herself as “the eternally consummate virgin Saint Mary, mother of the very true deity, God, the giver of life, the creator of people, the ever present, the Lord of heaven and earth.” She then asked Juan Diego to relate to the bishop her wish for a Church to be built on that very spot, where she would attend to the “weeping and sorrows of you and all the people of this land, and of the various peoples who love me…”

Juan Diego rushed the final miles on foot and waited for hours to see Bishop Juan Zumarraga. The friars were reluctant to allow such an audience with their bishop. After all, Juan Diego was a poor Indian, with a large poncho (tilma) and sandals on his feet, holding a walking stick with no appointment to see the bishop. He would need one of the friars to translate for him to speak with the Bishop. After waiting patiently, Juan Diego was finally ushered in. When he related his story to Bishop Zumarraga, Juan Diego, through the translator, was told that he needed a sign to prove that this account was true. A series of other events happened to Juan Diego over the next three days that would take too long here to explain, but then on December 12, 1531, Mary provided a sign that convinced the bishop that Juan Diego spoke the truth.

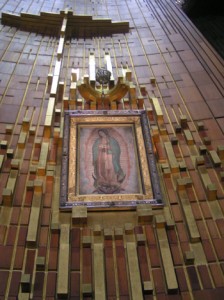

In his final encounter with Our Lady of Guadalupe, on December 12, Mary directed Juan to pick some flowers from the top of Tepeyac hill. Remember it was December at high elevation, flowers are not known to grow that time of year there. The flowers turned out to be roses which were not indigenous to Mexico, but were known to the Spanish of course. Mary arranged the roses herself and instructed Juan to keep the flowers hidden until he saw the bishop again. When Juan Diego returned to the bishop and opened his cloak to show the flowers, Bishop Juan and all those present were amazed and fell prostrate. The roses were only part of the miracle. Emblazoned somehow onto Juan Diego’s tilma was the image that we know today as Our Lady of Guadalupe.

The image turned out to be the key for the Aztecs to understand the One True God. In one miraculous image, Mary explained her role in the Church and the way to God. This is how the image helped the Aztecs and others without a written language to understand:

Our Lady of Guadalupe was not a god herself, in fact she was standing in front of what appeared to the Aztecs their sun god, something no-one would dare do. Her eyes looked down, not straight ahead as all Aztec gods did. For the Spanish, the luminous light surrounding the Lady was reminiscent of the “woman clothed with the sun” of Revelation 12:1. The rays of the sun would also be recognized by the Aztecs and other indigenous people as a symbol of their highest god, Huitzilopochtli. Thus, the lady comes forth hiding but not extinguishing the power of the sun.

Mary stood upon the moon. Again, the symbolism was that of the woman of Revelation 12:1 who has the “moon under her feet.” The moon for the Aztecs was the god of the night. By standing on the moon, she shows that she was more powerful than the Aztec god of darkness.

The eyes of Our Lady of Guadalupe looked down with humility and compassion. This was a sign to the Aztecs that she was not a god since in their iconography the gods stare straight ahead with their eyes wide open.

The angel supporting the Lady testified to her royalty. To the Aztecs, only kings, queens and other dignitaries were carried on the shoulders of someone. The mantle of the Lady was blue-green or turquoise. To the Aztecs, this was the color of the gods and of royalty. The stars on Mary’s mantle indicated that she came down from heaven.

The brown bow around her waist was a sign of her virginity, but it also had several other meanings. The bow appears as a four-petaled flower. To the Aztecs, this was the nahui ollin, the flower of the sun, a symbol of plenitude. For them, this was the symbol of creation and new life and so by Mary’s dress, the image shows that she was of royalty from heaven and was both a virgin and “with child.”

Soon a chapel was built as requested, and the image was copied for others to see. As the Aztecs and other tribal members saw the image, they asked to be baptized in the Catholic Faith. This was the true miracle, the one of conversion. In less than twenty years, nine million of the inhabitants of the land, who professed for centuries a polytheistic and human-sacrificing religion, were converted to the Catholic Faith.

Have we traded cultures of death in 2017?

Five centuries later we can be thankful that no society has risen from ashes of the Aztecs to reclaim as a basic religious right the slaughter of innocent people. We have advanced as a world and no longer tolerate the practice of human sacrifice. The Aztecs and other cultures before them were convinced of the need to slaughter human beings in order for their society to survive. In the Aztec society the brightest, most well-trained leaders, the royalty, the priestly class and the entire culture were convinced of the need to kill innocent people atop those pyramids for thousands of years. Over the centuries throughout the Americas, tens of millions were killed in the name of all their false gods.

And yet if we look at our culture today in the twenty-first century, have we traded ourselves for false gods again? Today in America, some of the brightest, best-trained leaders and most protestant churches believe it is the right of a woman to murder innocent human beings in their own wombs. The odds in Aztec society of being a human sacrifice victim were probably about one in five according to historians. Today in our culture, nearly twenty percent of all pregnancies end in abortion and about forty percent of all unintended pregnancies. Once you are slaughtered by abortion, your unique DNA and your tiny body parts are farmed out to be used for everything from testing cosmetics to conducting biomedical experiments. Or some aborted babies uniqueness is used as the the growing agent for required vaccines. Our society uses and depends on the slaughter of tens of millions of innocent human beings, just as the Aztecs once did; we cannot survive this any more than they did.

It is a sad, bloody road we have traveled back these past five centuries later. A society that does not value its most innocent people, cannot survive ultimately.

Jesus sent his Mother once to triumph over the false gods that the Aztecs were worshipping and to put an end to the culture of brutal human sacrifice. Mary ended that Aztec culture of death once and for all. We can surely trust that Our Lady will intervene for us and overwhelm the darkness with the brightness of her presence once again. On this Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, let us pray for her intervention to bring an end to the deadly errors in our society that lead us into the darkness of death once again. Hail Mary, full of grace! Pray today that Mary, the protector of the Americas and the unborn will once again triumph and defeat our modern practice of human sacrifice.